Targeting the E3 ligase RLIM to regulate VSMC phenotypic switching in vascular aging: implications for cold stress

doi: 10.1515/fzm-2025-0018

-

Abstract:

Objective Cold exposure may impair vascular function and promote cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) by causing vasoconstriction, hemodynamic changes, and sympathetic activation. Vascular aging, a key factor in CVDs, is linked to phenotypic switching of vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs), but its regulatory mechanisms are not fully understood. Materials and methods We used aged C57BL/6 mice and D-galactose-induced senescent VSMCs to investigate the role of the E3 ligase RLIM in arterial aging. RLIM knockdown and overexpression in vivo were achieved using adenoassociated virus (AAV) vectors. Vascular aging and stiffness were assessed using β-galactosidase staining, pulse wave velocity (PWV) measurements, and histological staining. Proteomic profiling was conducted to identify key protein alterations associated with vascular dysfunction and to elucidate underlying mechanisms. Results RLIM expression was significantly upregulated in the aortae of aged mice and D-galactose-induced senescent VSMCs. AAV-mediated RLIM knockdown significantly attenuated vascular aging, as evidenced by vascular ultrasound and histological assessments. Conversely, RLIM overexpression exacerbated vascular damage. Proteomic analysis revealed that RLIM knockdown in VSMCs from aged mice resulted in increased expression of smooth muscle contractile proteins and decreased levels of inflammatory markers, indicating a phenotypic shift toward a more contractile state. Conclusion These findings identify RLIM as a key regulator of arterial aging and a promising therapeutic target for age-related cardiovascular diseases. -

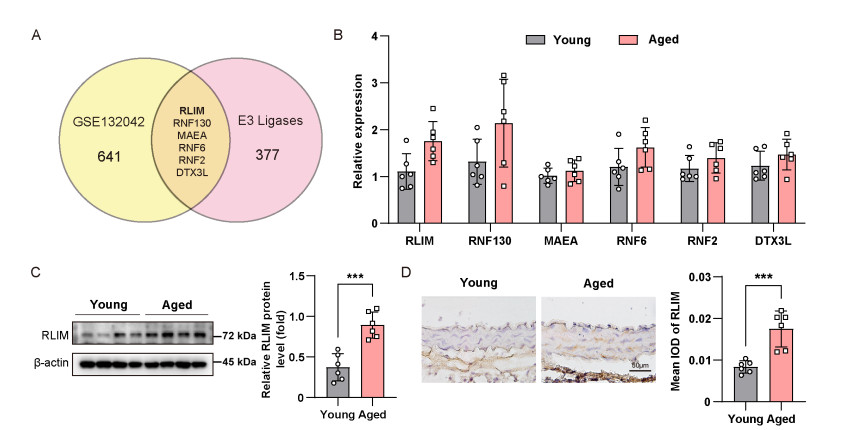

Figure 1. Elevated expression of ring finger protein-LIM domain interacting (RLIM) in aortic tissues from aged mice

(A) Venn diagram showing six differentially expressed E3 ligases in aortic vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs) from young and aged mice based on Tabula Muris Senis single-cell RNA-seq data. (B) qRT-PCR analysis of selected E3 ligases in aortae of young and aged mice. (C) Western blot analysis of RLIM protein levels in aortic tissues. (D) Immunohistochemistry showing increased RLIM expression in the medial layer of aged aortic sections. Scale bars, 50 μm. Statistical differences were ana-lyzed using an unpaired Student's t-test. N = 6 per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. ***P < 0.001.

Figure 2. Upregulation of ring finger protein-LIM domain interacting (RLIM) in D-galactose-induced senescence of mouse vascular smooth muscle cells (MOVAS) cells

(A) SA-β-gal staining of MOVAS cells treated with 0, 5, 25, or 50 mmol/L D-galactose for 12, 24, 36, or 48 hours. Quantification of SA-β-gal-positive cells is shown in the line graph. Scale bars, 50 μm. (B) Cell counting kit-8 (CCK-8) assay at different D-galactose concentrations and time points. (C) EdU incorporation assay assessing cell proliferation in control and D-galactose-treated MOVAS cells. Scale bars, 50 μm. (D) Western blot analysis of RLIM, p21, and p16 expression in MOVAS cells treat-ed with D-galactose compared to control. Statistical comparisons were performed using unpaired Student's t-test. N = 3-5 per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001.

Figure 3. Effects of ring finger protein-LIM domain interacting (RLIM) knockdown on vascular aging in young and aged mice

(A) Experimental timeline for adenoassociated virus (AAV)9-SM22α-shRLIM injection in young (3-month) and aged (18-month) mice. (B) SA-β-gal staining of aortae from young and aged mice treated with AAV9-SM22α-shRLIM or vector control. (C) Pulse wave velocity (PWV) measurements in the aortic arch and left common carotid artery of young and aged mice following RLIM knockdown in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). (D) Treadmill performance in young and aged mice with or without RLIM knockdown in VSMCs. (E) Histological images of aortic sections stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H & E), elastica-van-gieson (EVG), and Masson's trichrome in RLIM knockdown and control mice. Scale bars, 50 μm. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student's t-test. N = 6 per group. Data are pre-sented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.017, **P < 0.003, ***P < 0.0003 after Bonferroni correction.

Figure 4. Effects of ring finger protein-LIM domain interacting (RLIM) overexpression on vascular aging and function in young and aged mice

(A) Experimental timeline of adenoassociated virus (AAV)9-SM22α-RLIM injections in young (3-month) and aged (18-month) mice. (B) Representative SA-β-gal stain-ing of aortic tissues from young and aged mice treated with AAV9-SM22α-RLIM or vector control. (C) Pulse wave velocity (PWV) measurements in the aortic arch and left common carotid artery of young and aged mice with or without RLIM overexpression in vascular smooth muscle cells (VSMCs). (D) Treadmill performance in young and aged mice following RLIM overexpression in VSMCs. (E) Histological staining hematoxylin and eosin (H & E), elastica-Van-Gieson (EVG), Masson's trichrome of aortic sections in RLIM-overexpressing and control mice. Scale bars, 50 μm. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student's t-test. N = 6 per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.017, **P < 0.003, ***P < 0.0003 after Bonferroni correction for multiple comparisons.

Figure 5. Proteomic analysis of aortic tissue from aged mice with vascular smooth muscle cell (VSMC)-specific ring finger protein-LIM domain interacting (RLIM) knockdown

(A-B) Heatmap (A) and volcano plot (B) showing differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) in the aortae of aged mice treated with adenoassociated virus (AAV)9-SM22α-shRLIM compared to control mice, based on P < 0.05 and |log2 fold change| ≥ 0.585. (C) Kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes (KEGG) pathway enrich-ment analysis of DEPs. Bubble size indicates the number of proteins involved in each pathway; color gradient represents statistical significance. (D) Heatmap of DEPs involved in smooth muscle contraction, cell cycle regulation, autophagy, and inflammation. (E) Venn diagram illustrating the overlap between DEPs and predicted RLIM ubiquitination substrates from the Ubibrowser 2.0 database. (F) Immunohistochemical staining of CSRP2 in aortic sections from young and aged mice with or without RLIM knockdown in VSMCs. Scale bars, 50 μm. Statistical analysis was performed using unpaired Student's t-test. N = 6 per group. Data are expressed as mean ± SD. *P < 0.017, **P < 0.003, ***P < 0.0003 after Bonferroni correction.

-

[1] Song X, Wang S, Hu Y, et al. Impact of ambient temperature on morbidity and mortality: An overview of reviews. Sci Total Environ, 2017; 586: 241-254. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.01.212 [2] Bunker A, Wildenhain J, Vandenbergh A, et al. Effects of air temperature on climate-sensitive mortality and morbidity outcomes in the elderly; a systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological evidence. EBioMedicine, 2016; 6: 258-268. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2016.02.034 [3] Liu C, Yavar Z, Sun Q. Cardiovascular response to thermoregulatory challenges. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol, 2015; 309(11): H1793-H1812. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00199.2015 [4] Fares A. Winter cardiovascular diseases phenomenon. N Am J Med Sci, 2013; 5(4): 266-279. doi: 10.4103/1947-2714.110430 [5] Shepherd J T, Rusch N J, Vanhoutte P M. Effect of cold on the blood vessel wall. Gen Pharmacol, 1983; 14(1): 61-64. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(83)90064-2 [6] Hess K L, Wilson T E, Sauder C L, et al. Aging affects the cardiovascular responses to cold stress in humans. J Appl Physiol (1985), 2009; 107(4): 1076-1082. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00605.2009 [7] Dong M, Yang X, Lim S, et al. Cold exposure promotes atherosclerotic plaque growth and instability via UCP1-dependent lipolysis. Cell Metab, 2013; 18(1): 118-129. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.06.003 [8] van Bergen P, Fregly M J, Rossi F, et al. The effect of intermittent exposure to cold on the development of hypertension in the rat. Am J Hypertens, 1992; 5(8): 548-555. doi: 10.1093/ajh/5.8.548 [9] Fu S, Cao Y, Li Y. [Epidemiological study of hypertension in Heilongjiang province]. Zhonghua Nei Ke Za Zhi, 2022; 41: 114-116. [10] Kontis V, Bennett J E, Mathers C D, et al. Future life expectancy in 35 industrialised countries: projections with a Bayesian model ensemble. Lancet, 2017; 389(10076): 1323-1335. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(16)32381-9 [11] Department of Economic and Social Affairs. Leaving no one behind in an ageing world (World Social Report 2023). New York: World Population Ageing, 2019. [12] Yazdanyar A, Newman A B. The burden of cardiovascular disease in the elderly: morbidity, mortality, and costs. Clin Geriatr Med, 2009; 25(4): 563-vii. doi: 10.1016/j.cger.2009.07.007 [13] Fajemiroye J O, da Cunha L C, Saavedra-Rodríguez R, et al. Aging-induced biological changes and cardiovascular diseases. Biomed Res Int, 2018; 2018: 7156435. doi: 10.1155/2018/7156435 [14] Laurent S. Defining vascular aging and cardiovascular risk. J Hypertens, 2012; 30 Suppl: S3-S8. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328353e501 [15] Ungvari Z, Tarantini S, Kiss T, et al. Endothelial dysfunction and angiogenesis impairment in the ageing vasculature. Nat Rev Cardiol, 2018; 15(9): 555-565. doi: 10.1038/s41569-018-0030-z [16] Lacolley P, Regnault V, Nicoletti A, et al. The vascular smooth muscle cell in arterial pathology: a cell that can take on multiple roles. Cardiovasc Res, 2012; 95(2): 194-204. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs135 [17] Abdellatif M, Sedej S, Carmona-Gutierrez D, et al. Autophagy in cardiovascular aging. Circ Res, 2018; 123(7): 803-824. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.312208 [18] Wang J C, Bennett M. Aging and atherosclerosis: mechanisms, functional consequences, and potential therapeutics for cellular senescence. Circ Res, 2012; 111(2): 245-259. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.261388 [19] Mian O, Santi N, Boodhwani M, et al. Arterial age and early vascular aging, but not chronological age, are associated with faster thoracic aortic aneurysm growth. J Am Heart Assoc, 2023; 12(16): e029466. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.122.029466 [20] Matsumoto T, Watanabe S, Ando M, et al. Diabetes and age-related differences in vascular function of renal artery: possible involvement of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Rejuvenation Res, 2016; 19(1): 41-52. doi: 10.1089/rej.2015.1662 [21] Lacolley P, Regnault V, Avolio A P. Smooth muscle cell and arterial aging: basic and clinical aspects. Cardiovasc Res, 2018; 114(4): 513528. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvy009 [22] Owens G K, Kumar M S, Wamhoff B R. Molecular regulation of vascular smooth muscle cell differentiation in development and disease. Physiol Rev, 2004; 84(3): 767-801. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2003 [23] Monk B A, George S J. The Effect of ageing on vascular smooth muscle cell behaviour--a mini-review. Gerontology, 2015; 61(5): 416-426. doi: 10.1159/000368576 [24] Wang L, Wang M, Niu H, et al. Cholesterol-induced HRD1 reduction accelerates vascular smooth muscle cell senescence via stimulation of endoplasmic reticulum stress-induced reactive oxygen species. J Mol Cell Cardiol, 2024; 187: 51-64. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2023.12.007 [25] Miao S B, Xie X L, Yin Y J, et al. Accumulation of smooth muscle 22α protein accelerates senescence of vascular smooth muscle cells via stabilization of p53 in vitro and in vivo. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol, 2017; 37(10): 1849-1859. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.117.309378 [26] Wang F, Bach I. Rlim/Rnf12, Rex1, and X chromosome inactivation. Front Cell Dev Biol, 2019; 7: 258. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2019.00258 [27] Huang Y, Nie M, Li C, et al. RLIM suppresses hepatocellular carcinogenesis by up-regulating p15 and p21. Oncotarget, 2017; 8(47): 83075-83087. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.20904 [28] Gao K, Wang C, Jin X, et al. RNF12 promotes p53-dependent cell growth suppression and apoptosis by targeting MDM2 for destruction. Cancer Lett, 2016; 375(1): 133-141. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.02.013 [29] Gao R, Wang L, Cai H, et al. E3 ubiquitin ligase RLIM negatively regulates c-Myc transcriptional activity and restrains cell proliferation. PLoS One, 2016; 11(9): e0164086. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0164086 [30] Her Y R, Chung I K. Ubiquitin ligase RLIM modulates telomere length homeostasis through a proteolysis of TRF1. J Biol Chem, 2009; 284(13): 8557-8566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806702200 [31] Zhang L, Huang H, Zhou F, et al. RNF12 controls embryonic stem cell fate and morphogenesis in zebrafish embryos by targeting Smad7 for degradation. Mol Cell, 2012; 46(5): 650-661 doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.04.003 [32] Tabula Muris Consortium. A single-cell transcriptomic atlas characterizes ageing tissues in the mouse. Nature, 2020; 583(7817): 590-595. doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2496-1 [33] Frismantiene A, Philippova M, Erne P, et al. Smooth muscle cell-driven vascular diseases and molecular mechanisms of VSMC plasticity. Cell Signal, 2018; 52: 48-64. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2018.08.019 [34] Zhang M J, Zhou Y, Chen L, et al. An overview of potential molecular mechanisms involved in VSMC phenotypic modulation. Histochem Cell Biol, 2016; 145(2): 119-130. doi: 10.1007/s00418-015-1386-3 [35] Chi C, Li D J, Jiang Y J, et al. Vascular smooth muscle cell senescence and age-related diseases: State of the art. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis, 2019; 1865(7): 1810-1821. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.08.015 [36] Uryga A K, Bennett M R. Ageing induced vascular smooth muscle cell senescence in atherosclerosis. J Physiol, 2016; 594(8): 2115-2124. doi: 10.1113/JP270923 [37] Ungvari Z, Tarantini S, Donato A J, et al. Mechanisms of vascular aging. Circ Res, 2018; 123(7): 849-867. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.118.311378 [38] Callis J. The ubiquitination machinery of the ubiquitin system. Arabidopsis Book, 2014; 12: e0174. doi: 10.1199/tab.0174 [39] Pupo A, Fernández A, Low S H, et al. AAV vectors: the Rubik's cube of human gene therapy. Mol Ther, 2022; 30(12): 3515-3541. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2022.09.015 -

投稿系统

投稿系统

下载:

下载: